To ease potential confrontations between police and veterans, HPD started offering intensified PTSD awareness training this year.

By Lindsay Wise

The Houston Chronicle

(reposted by Michael Leon

Veteran's Today

December 14, 2010)

A veteran suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder runs a stop sign because he feels he’s being followed. A police officer pulls him over, and their interaction escalates into an argument. The veteran ends up in jail.

This scenario, recounted by Stacey Lanier, a staff psychologist at Houston’s Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, is a real-life example of misunderstandings between law enforcement officers and veterans returning from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan with amped-up anxiety, anger and post-traumatic stress.

Houston Police Department statistics show the number of veterans taken to the VA medical center for mental health treatment following calls for service has jumped from just four in 2007 to 64 in 2009.

The veteran who ran the stop sign was having a paranoid reaction, Lanier said.

“He was agitated, and he was trying to explain what was happening from his perspective, and the officer just thought he was trying to make excuses,” she said. “And that was a case where there was no need for that.”

To ease potential confrontations between police and veterans, HPD started offering intensified PTSD awareness training this year.

“I absolutely think that there’s a need for it because people tend to pathologize people with PTSD rather than seeing that they’re regular people who are hypersensitive to danger,” Lanier said.

Crisis training

About 40 percent of HPD’s patrol officers have received crisis intervention training, which became mandatory for all cadets in 2007, said Frank Webb, a senior officer with HPD’s Mental Health Unit.

The training previously included a segment on PTSD, but this year, the department supplemented the training with longer and more comprehensive classes. The sessions feature veterans diagnosed with PTSD, VA psychologists, and officials from the city of Houston’s Office of Veterans Affairs.

“Most of what we do is very physical, authoritative, commanding,” Webb said. Such tactics can backfire when confronting someone who has PTSD, he said, so crisis intervention training teaches officers to use de-escalation techniques instead. “It’s the step back, it’s the patience, it’s allowing people to ventilate,” he said. “It’s almost the opposite, but it works much better.”

Veterans don’t get a free pass, Webb said, but police officers should treat them with respect, thank them for their service, “and most importantly, if the officer has any experience as a veteran, try to use that experience to connect with the veteran.”

Interpreting behavior

Harris County is home to nearly 200,000 veterans, including about 18,000 who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. As many as one in five Iraq and Afghanistan veterans struggle with PTSD, according to VA’s National Center for PTSD.

In classes with HPD cadets, Lanier explains the symptoms and causes of PTSD and gives examples of ways that veteran behavior has been misinterpreted by officers.

A veteran might suddenly swerve over three lanes to avoid a large piece of trash on the highway because his battle-honed instincts tell him the debris could be hiding a roadside bomb, she said. However, a police officer could interpret the veteran’s erratic behavior as drunken driving or just driving with no regard for the law.

Lanier advises police not to take an aggressive stance with veterans or to touch them, if avoidable.

“For combat veterans, somebody getting into their physical space is a threat and they’re going to become more agitated,” she said. “It might be better to just talk to them and give them their space.”

Haunted by deaths

During a recent training session at the police academy, a rapt audience of officers listened to decorated Iraq war veteran Marty Gonzalez describe life with PTSD, and his own run-in with the law.

“I wasn’t sleeping right, I wasn’t eating right, I wasn’t doing anything right,” said the 30-year-old retired Marine sergeant from The Woodlands, who earned two Bronze Stars for valor and three Purple Hearts in Iraq. “Asking for help wasn’t really an option. I just sucked it up.”

Gonzalez was haunted by the deaths of 18 men in his battalion, including four from his platoon. He pushed away his family and eventually separated from his wife.

"Arguing all the time, drinking all the time,” he recalled. “I was on all kinds of different medicines. Seventeen different pills through VA.”

2008 auto wreck

Gonzalez’s wake-up call came in 2008 when he got behind the wheel after taking too many prescription pain killers. He crashed his car into the living room of his house. No one was hurt, but Gonzalez knew the outcome could’ve been much worse. His 2-year-old son had been in the backseat.

He’s since completed two years of probation and court-ordered treatment for felony charges of driving while intoxicated.

“You lose your way,” Gonzalez told the class of veteran officers at the academy this week. “I had to really start getting God in my life and letting Him take over: ‘It’s OK you lost your men. They don’t want to trade places with you. You’re here for a purpose.’ And apparently part of my purpose is trying to help you guys understand veterans better.”

‘It’s a good outlet’

Gonzalez seemed embarrassed by the loud applause at the end of his talk. As the officers filed from the classroom, many stopped to shake his hand and thank him for his service. About a third were veterans themselves, and identified personally with his story.

“We’ve had officers in this class who just come out and say, ‘Hey, I’ve got PTSD,’ ” Webb said. “It’s like their opportunity to vent and talk about it. I think it’s a good outlet for them.”

Sue Lamoureux's blog for her husband, J Patrick Lamoureux. Sue died on 24 August 2015.

PAT LAMOUREUX

PAT LAMOUREUX - One episode in a person's life, does not define the person.

Monday, January 10, 2011

Crisis Intervention Training of Police to ease confrontations with Veterans

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

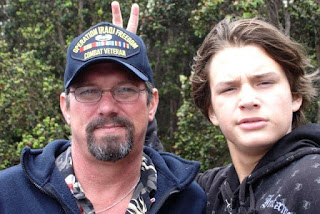

"Grandpa Pat & Kain"

"Kain-man" the jokester....

Pat Lamoureux - Iraq 2003

"Pat is an extraordinary, thoughtful, kind and generous man...not to mention a wonderful friend, in which one could always count upon to be there when in need." (words of a long time friend)

Pat's Family

Mica & Heather, grandson Kain

No comments:

Post a Comment