Sue Lamoureux's blog for her husband, J Patrick Lamoureux. Sue died on 24 August 2015.

PAT LAMOUREUX

PAT LAMOUREUX - One episode in a person's life, does not define the person.

Friday, November 6, 2009

Vicarious traumatization: PTSD is contagious and deadly

Simu-Nation

Nov. 5 2009 - 10:03 pm

All the facts about the Fort Hood massacre are not in yet, and may not be for some time. The early facts left me horrified, and a little scared: Terrorism? Warriors run amuck? But when I learned that the likely shooter was an Army psychiatrist who treats PTSD, himself on the cusp of deployment, I thought, “I’m not surprised.”

One fact we do know is that treating PTSD is itself traumatic. Before you judge or maybe make a joke about some shrink wigging out–or indulge ugly racist fantasies–I want you to imagine a work day spent bearing witness to traumas so horrific media outlets won’t even show the videos. Imagine every day trying to help young men and women somehow put their lives back together despite their night terrors, flashbacks, and chronic sleeplessness. While you reach out to help, they mistrust your every move and respond with hair-trigger tempers, not to mention all the physical symptoms, alienation, and hopelessness. Surrounded by thoughts of suicide–and homicide–you try and keep faith with the honor and challenge of providing care.

But soon the line between their experience and yours starts to blur until, well, something like what happened at Fort Hood today becomes an all too real possibility.

The fact is treating soldiers traumatized by war experience is not just an honor and a challenge; it is itself a risky behavior. McCann and Pearlman, in a 1990 article in the Journal of Traumatic Stress were the first to identify:

(click here for complete article)

Thursday, November 5, 2009

Is This Any Way to Treat Our Heroes?

Posted: October 30, 2009 06:00 PM BIO

"This is where we are failing our heroes and veterans. How can Congress pass a $680 billion defense authorization bill on October 22, 2009 to keep spending money and sending soldiers to die or be maimed overseas and not allocate enough for their recovery when they return?"

A close family friend's son recently returned from Afghanistan where he had been working as a government contractor for the US war there. He is a Veteran Marine who joined in 2002 right after terrorists flew airplanes into the World Trade Center buildings on 9/11/01. He unselfishly wanted to serve his country and defend us from these attacks.

He was readily accepted by the United States Marine Corp. and his fellow soldiers, having been voted #1 Honor Man of his boot camp even though he was at least 10 years older than most of his peers. He worked his way up to Staff Sergeant and was so well liked by his battalion that they resisted sending him out to the battlefield. They didn't want to lose him.

But go to war he did with tours in both Iraq and Afghanistan. He served proudly with many honors and awards until 2006 when he started contract work in Afghanistan.

He has a wife and young son, two parents and a sister who love him dearly. You can imagine his family's sense of relief every time he returned home safely and in one piece after each tour of duty. His last trip home in September of this year seemed as any other, but then something very strange and frightening happened. He tried to commit suicide by shooting himself in the head. Luckily, he was a bad shot and survived, ending up needing surgery to repair his eye socket, but the emotional damage is the harder part to heal. We are told he is suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) which afflicts many soldiers and anyone who has been in life threatening situations. We can only imagine what horrors he has endured being in a war zone off and on for over six years.

Read more at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/joan-e-dowlin/is-this-any-way-to-treat_b_336047.html.

Sunday, November 1, 2009

Trauma in Iraq leads to drama in Oregon

October 31, 2009, 3:00PM

(Editor's note - Details of the crime and quotes are from testimony ini Grant County Circuit Court. Other reporting includes interviews with witnesses, families, police, Oregon Department of Corrections, attorneys and Department of Veterans Affairs reports.)

"And last month, a Grant County jury considered how much war changed Jessie Bratcher. For the first time in Oregon, and among the first cases nationwide, post-traumatic stress from serving in Iraq was the defense for murder."

JOHN DAY -- Later, after the defense attorney wept and the judge put away his robe and the jurors drove home in the fading light, the consequences of war hung over this town of 1,845 like wood smoke on an autumn eve.

Fourteen months earlier, a young woman lay down with a terrible burden. She was pregnant. Her fiancé, Jessie Bratcher, was so thrilled he kissed the home pregnancy test kit. He researched how a baby develops and what the mother should eat.

But Celena Davis was not sure the child was his.

As Bratcher sat on the foot of their bed, she told him that two months earlier, she had been raped.

The Iraq veteran dropped to his knees and cried. Bratcher went to the living room and put the barrel of an AK-47 in his mouth, then stopped. He grabbed scissors and cut off half of Celena's long dark hair. They stayed up all night. When she complained of cramps, he walked her to the hospital at 6 a.m., so tense that nurses shooed him away.

He returned for her in his pickup and drove east to Boise. They went to a movie, "The Dark Knight." He had "Celena" tattooed on his arm and they returned home late.

By 9 the next morning, Aug. 16, 2008, Bratcher shook Celena, "Get up, get up." He wanted to confront the man she identified as the rapist. Bratcher drove to Ace Hardware, paid $10 for a background check and bought a .45-caliber semiautomatic handgun with extra ammo.

He was shaking.

Back in the truck, as he jammed bullets into the magazine, Bratcher told Celena she had a choice: go to the police or confront Jose Ceja Medina.

"Police," she said.

But it was Saturday and the John Day police station was locked. Dispatchers inside saw the couple try the door, then leave. Minutes later, they stood in an open doorway of Ceja Medina's home.

His nephew, Fernando Ceja, a Prairie High ninth-grader, was inside messaging friends on MySpace. He fetched his uncle, doing laundry down the hall. Ceja Medina wore only running shorts.

The three adults stood in the yard, shouting. Celena cried uncontrollably. Ceja Medina denied knowing her. Then, he said it was sex, not rape. If there was a child, he said, he would take responsibility.

Bratcher pulled the gun from his back pocket and fired 10 times as Ceja Medina ran, hitting him in the buttocks, hip, waist, shin and, fatally, in the head.

A neighbor heard it: "Boom, boom, boom, boom, boom ... ."

War has changed the Oregon Army National Guard, which has deployed troops on 8,400 tours in Iraq and Afghanistan since 9/11. It turned the state's emergency volunteers into combat veterans.

And last month, a Grant County jury considered how much war changed Jessie Bratcher. For the first time in Oregon, and among the first cases nationwide, post-traumatic stress from serving in Iraq was the defense for murder.

Testimony in the nine-day trial in Canyon City, three miles from the death scene, revealed how years after a soldier deployed, the invisible wounds of war led to the town's first murder trial since 1992.

Bratcher was raised by his grandfather Jerry Baughman in Prairie City. "He's my grandson and my son both. I raised him from the time he was a little boy. I don't ever use the word step. That step, it's a dirty word, so I call him my real son."

Since Bratcher was a boy, he worked, splitting and stacking the wood that his granddad sawed. They hunted together, "though he would rather I do the shooting," Baughman said. "He didn't actually care for killing anything."

At Blue Mountain Alternative High School, "Jessie was a peacemaker. That's how I would have to define him," said teacher Crish Hamilton. "Jessie would not instigate a fight but would try to cool the parties down, and I can say that because he did that fairly often."

Bratcher joined the Oregon Guard in 2002 in a surge of patriotism and a vague plan to get an education. By Thanksgiving 2004 he was in Iraq, one of 400 soldiers from the 3rd Battalion, 116th Armored Cavalry Regiment out of eastern Oregon. The "M-1 Tankers" retrained for six months as infantry before an 11-month deployment.

In Iraq they policed 96 villages around Kirkuk, patrolling in Humvees and on foot. Insurgents lobbed mortars into their base, which triggered counterattacks by U.S. artillery. Outside the base, roadside bombs awaited, from hand grenades to car bombs.

"It was very difficult to defend against," said Bratcher's team leader, now retired, Staff Sgt. Johnny Torres. "In training, we were told what to look for, but once we rolled into country, the whole country was a garbage dump. It was next to impossible to pinpoint where they were."

Bratcher ran into trouble with his first squad after he refused to shoot at people he couldn't identify as enemies, and filed an incident report that differed sharply from other soldiers'.

"The other individuals were basically trying to cover up," said Martin Castellanoz, his platoon sergeant. "He told us the truth."

After, the others bullied Bratcher, so Castellanoz put him in a squad with his close friend, Oregon corrections officer John Ogburn III.

"They were good-hearted guys," Castellanoz said. "They were the ones going to church together, to chow together, everyone was helping everyone."

On May 22, 2005, an Iraqi truck veered into their patrol convoy, forcing Ogburn's Humvee to swerve. The vehicle rolled. Ogburn, the turret gunner, was crushed as Bratcher and the others watched. Bratcher, who later helped load his friend's casket onto the plane home, withdrew after that, his sergeant said.

Five weeks later Bratcher's Humvee was hit at the same intersection by a roadside bomb. At first the team reported no injuries, though Bratcher and his team leader both had headaches. The team leader learned in 2008 that his recurring anxiety, depression and mood swings were traumatic brain injury from the blast -- symptoms which overlap and mimic post-traumatic stress disorder.

"Inside I don't feel like I've changed, but my ex-wife says I've changed too much," said the team leader, Torres. "That's what she said when she left this year." He described his anger as "almost instantaneous. Almost like a light switch."

(click here for complete story) http://www.oregonlive.com/news/index.ssf/2009/10/post_25.html

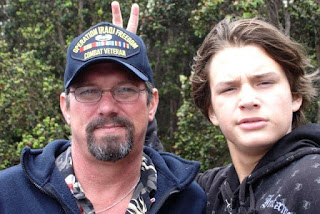

"Grandpa Pat & Kain"

"Kain-man" the jokester....

Pat Lamoureux - Iraq 2003

"Pat is an extraordinary, thoughtful, kind and generous man...not to mention a wonderful friend, in which one could always count upon to be there when in need." (words of a long time friend)

Pat's Family

Mica & Heather, grandson Kain