NY Times

By JAMES DAO and DAN FROSCH

Published: April 24, 2010

COLORADO SPRINGS — A year ago, Specialist Michael Crawford wanted nothing more than to get into Fort Carson’s Warrior Transition Battalion, a special unit created to provide closely managed care for soldiers with physical wounds and severe psychological trauma. A strapping Army sniper who once brimmed with confidence, he had returned emotionally broken from Iraq, where he suffered two concussions from roadside bombs and watched several platoon mates burn to death. The transition unit at Fort Carson, outside Colorado Springs, seemed the surest way to keep suicidal thoughts at bay, his mother thought.

It did not work. He was prescribed a laundry list of medications for anxiety, nightmares, depression and headaches that made him feel listless and disoriented. His once-a-week session with a nurse case manager seemed grossly inadequate to him. And noncommissioned officers — soldiers supervising the unit — harangued or disciplined him when he arrived late to formation or violated rules.

Last August, Specialist Crawford attempted suicide with a bottle of whiskey and an overdose of painkillers. By the end of last year, he was begging to get out of the unit.

“It is just a dark place,” said the soldier, who is waiting to be medically discharged from the Army. “Being in the W.T.U. is worse than being in Iraq.”

(Click here for complete article: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/25/health/25warrior.html?emc=eta1 )

Sue Lamoureux's blog for her husband, J Patrick Lamoureux. Sue died on 24 August 2015.

PAT LAMOUREUX

PAT LAMOUREUX - One episode in a person's life, does not define the person.

Monday, April 26, 2010

From combat to lockdown: Troubled veterans trading military uniforms for prison attire

(Note from SUE: I am not condoning the actions of Veterans who are repeat offenders, do not interpret it that way.)

Prisons do not offer effective treatment for PTSD. Utah Department of Corrections therapist Ross Williams said, "The priority here is safety and security, not treatment,'' Williams said. "We do enough to keep people stable and healthy enough to do their time. We don't do enough to get people healed and well."

By Matthew D. LaPlante

The Salt Lake Tribune

Updated: 04/25/2010 10:15:18 AM MDT

John Pace stumbled to his car, slipped Johnny Cash's "Folsom Prison Blues" into the compact disc player and turned the key.

From half a century away, one Air Force veteran crooned to another:

When I was just a baby, my mama told me, 'Son, Always be a good boy, don't ever play with guns.'

Five years as a military police officer, including a stint in South Korea, a tour of duty in Afghanistan and multiple deployments in Iraq, had all come to this: a drunken 23-year-old combat vet behind the wheel, determined to find another bottle to empty onto his pain.

Pace pulled into the dark parking lot of a TGI Friday's restaurant in Riverdale, broke a window and crawled inside. He took one bottle, then another. Then he decided to empty out the entire bar.

More than 2 million American military members have served in the nation's ongoing conflicts, and many are returning home deeply troubled by their experiences. About a third suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), traumatic brain injury, depression or other mental illness. At least a fifth struggle with drug or alcohol dependency.

Mental illness and substance abuse are the greatest predictive factors for incarceration in America. And that has put thousands of veterans on a collision course with the nation's criminal justice system.

But no one has a handle on the extent of the problem because most police agencies, prosecutors and prisons aren't tracking who, among the accused and the convicted, has served in the military.

That lack of information is hampering criminal justice officials and social workers who are making an initial push to help veterans in Utah get the support they need before they wind up behind bars - especially if, like Pace, they have not committed a violent crime. But most vets in trouble with the law today will complete their sentences before help arrives.

'I let it get to this point' » Pace, who grew up in Atlanta, yearns for home. But he blames himself for where he is instead: the Central Utah Correctional Facility in Gunnison.

"I let it get to this point," he said. "I made the decisions that resulted in my being here."

Still, he adds, "I've got to give the military some credit, too. I can say with 100 percent certainty that I wouldn't be here if I hadn't gone to war."

Pace knew when he joined the Air Force, right after high school, that he was likely to be called into the fights in Afghanistan or Iraq. But his first tour of duty involved far less action. "In Korea, when we weren't working, we were drinking," he said. "That's just the way it is there."

Ultimately, Pace did deploy to Iraq -- where he manned combat checkpoints, stood watch on guard towers and ran convoys on bomb-laden roads, he said. Among his duty stations: Balad Air Base, not-so-fondly known as "Mortaritaville" for the frequency of mortar and rocket attacks, and Camp Bucca, where U.S. military police keep watch over thousands of Iraqi prisoners suspected of terrorist acts and other crimes.

He still has a hard time talking about his experiences, which left him troubled, confused and angry. "I started hitting the bottle as soon as I got out," Pace said.

Pace contends a desire to "feel a rush" -- like being at war -- drove his Oct. 3, 2008, restaurant break-in. He thinks medication for PTSD might have influenced his "stupid" decision. And alcohol did the rest.

For reasons he can't fully explain, most of the stolen bottles were at the bottom of a ravine near the Pineview Dam in Ogden Canyon within hours of the burglary.

"To see him like this is sad.' » It was Pace's first crime, and records show he cooperated with investigators who arrived on his doorstep the next morning. "I just wanted to avoid going to jail," he said.

"You've got to feel bad for the guy," said Riverdale Police Chief Dave Hansen. Pace had "a drinking problem -- and that certainly could be related to his time in the war," he said.

But charges were up to prosecutors, who filed two felonies against Pace in 2nd District Court. Five weeks later, Judge Ernie Jones - a retired lieutenant colonel in the Army Reserves - sentenced Pace to 36 months of probation for the theft.

A month later, Pace was back before Jones for hitting a parked car while driving drunk. Jones sent him to jail for 90 days with the admonition to use the time to sober up.

A few months after he got out of jail, police were called to an altercation between Pace and a female roommate. Pace wasn't charged in the incident, but he admitted he had been drinking -- a violation of the terms of his probation. On Feb. 11, Jones ordered Pace to prison for up to five years.

(click here for complete article: http://www.sltrib.com/Utah/ci_14948127 )

Prisons do not offer effective treatment for PTSD. Utah Department of Corrections therapist Ross Williams said, "The priority here is safety and security, not treatment,'' Williams said. "We do enough to keep people stable and healthy enough to do their time. We don't do enough to get people healed and well."

By Matthew D. LaPlante

The Salt Lake Tribune

Updated: 04/25/2010 10:15:18 AM MDT

John Pace stumbled to his car, slipped Johnny Cash's "Folsom Prison Blues" into the compact disc player and turned the key.

From half a century away, one Air Force veteran crooned to another:

When I was just a baby, my mama told me, 'Son, Always be a good boy, don't ever play with guns.'

Five years as a military police officer, including a stint in South Korea, a tour of duty in Afghanistan and multiple deployments in Iraq, had all come to this: a drunken 23-year-old combat vet behind the wheel, determined to find another bottle to empty onto his pain.

Pace pulled into the dark parking lot of a TGI Friday's restaurant in Riverdale, broke a window and crawled inside. He took one bottle, then another. Then he decided to empty out the entire bar.

More than 2 million American military members have served in the nation's ongoing conflicts, and many are returning home deeply troubled by their experiences. About a third suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), traumatic brain injury, depression or other mental illness. At least a fifth struggle with drug or alcohol dependency.

Mental illness and substance abuse are the greatest predictive factors for incarceration in America. And that has put thousands of veterans on a collision course with the nation's criminal justice system.

But no one has a handle on the extent of the problem because most police agencies, prosecutors and prisons aren't tracking who, among the accused and the convicted, has served in the military.

That lack of information is hampering criminal justice officials and social workers who are making an initial push to help veterans in Utah get the support they need before they wind up behind bars - especially if, like Pace, they have not committed a violent crime. But most vets in trouble with the law today will complete their sentences before help arrives.

'I let it get to this point' » Pace, who grew up in Atlanta, yearns for home. But he blames himself for where he is instead: the Central Utah Correctional Facility in Gunnison.

"I let it get to this point," he said. "I made the decisions that resulted in my being here."

Still, he adds, "I've got to give the military some credit, too. I can say with 100 percent certainty that I wouldn't be here if I hadn't gone to war."

Pace knew when he joined the Air Force, right after high school, that he was likely to be called into the fights in Afghanistan or Iraq. But his first tour of duty involved far less action. "In Korea, when we weren't working, we were drinking," he said. "That's just the way it is there."

Ultimately, Pace did deploy to Iraq -- where he manned combat checkpoints, stood watch on guard towers and ran convoys on bomb-laden roads, he said. Among his duty stations: Balad Air Base, not-so-fondly known as "Mortaritaville" for the frequency of mortar and rocket attacks, and Camp Bucca, where U.S. military police keep watch over thousands of Iraqi prisoners suspected of terrorist acts and other crimes.

He still has a hard time talking about his experiences, which left him troubled, confused and angry. "I started hitting the bottle as soon as I got out," Pace said.

Pace contends a desire to "feel a rush" -- like being at war -- drove his Oct. 3, 2008, restaurant break-in. He thinks medication for PTSD might have influenced his "stupid" decision. And alcohol did the rest.

For reasons he can't fully explain, most of the stolen bottles were at the bottom of a ravine near the Pineview Dam in Ogden Canyon within hours of the burglary.

"To see him like this is sad.' » It was Pace's first crime, and records show he cooperated with investigators who arrived on his doorstep the next morning. "I just wanted to avoid going to jail," he said.

"You've got to feel bad for the guy," said Riverdale Police Chief Dave Hansen. Pace had "a drinking problem -- and that certainly could be related to his time in the war," he said.

But charges were up to prosecutors, who filed two felonies against Pace in 2nd District Court. Five weeks later, Judge Ernie Jones - a retired lieutenant colonel in the Army Reserves - sentenced Pace to 36 months of probation for the theft.

A month later, Pace was back before Jones for hitting a parked car while driving drunk. Jones sent him to jail for 90 days with the admonition to use the time to sober up.

A few months after he got out of jail, police were called to an altercation between Pace and a female roommate. Pace wasn't charged in the incident, but he admitted he had been drinking -- a violation of the terms of his probation. On Feb. 11, Jones ordered Pace to prison for up to five years.

(click here for complete article: http://www.sltrib.com/Utah/ci_14948127 )

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

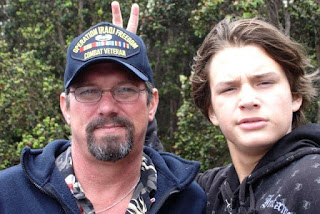

"Grandpa Pat & Kain"

"Kain-man" the jokester....

Pat Lamoureux - Iraq 2003

"Pat is an extraordinary, thoughtful, kind and generous man...not to mention a wonderful friend, in which one could always count upon to be there when in need." (words of a long time friend)

Pat's Family

Mica & Heather, grandson Kain