"OPINIONATOR-Exclusive on-line commentary from The Times"

February 6, 2010, 7:00 pm

By ERIK MALMSTROM

"In many ways, the culture shock of reintegrating into the civilian world was greater than that of joining the military. In a kind of reverse socialization, I had to make a concerted effort to modify my appearance, language and behavior."

Preparing for my part-time National Guard training, I am transported into a former life. Getting my old “number two on the sides and back, trim the top” haircut and putting on my digital camouflage uniform is like going through a time warp. Looking in the mirror, I feel as if I am staring at a person I used to be. Like a rusty foreign language speaker, I struggle to talk like a soldier. Once second nature, the clipped sentences and vocabulary of sirs, ma’ams, rogers, hoo-ahs, acronyms, four letter words and colorful expressions now take effort. I also return to a world where the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq are an impending reality, not a distant abstraction.

Over two years ago, I transitioned into the National Guard to complete my remaining service obligation. After four years of active duty, I made the difficult decision to get out of the military. While I loved the Army, professional and personal considerations prompted me to move on. I believed I could better affect the problems that I cared about by pursuing master’s degrees in public policy and business on the way to a civilian career. I also sought more balance, freedom and control in my life. The National Guard provided me flexibility to return to school while finishing my time in the military.

Previously, the active duty Army had dominated my life. It had been an all-consuming way of being and state of mind. I had lived in towns where people looked the same, talked the same and did the same things. The line between personal and professional had been blurred in the United States and nonexistent in Afghanistan. Work had become my life as I prepared and led my men overseas. I had prioritized it at the expense of everything else. It had also been segregated from my civilian life. My brief reprieves to visit family and friends had been like traveling to another universe.

(click below for complete article)

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/02/06/the-two-worlds-of-the-citizen-soldier/?emc=eta1.

Sue Lamoureux's blog for her husband, J Patrick Lamoureux. Sue died on 24 August 2015.

PAT LAMOUREUX

PAT LAMOUREUX - One episode in a person's life, does not define the person.

Tuesday, February 9, 2010

Monday, February 8, 2010

Call to Arms - Statham mom fighting for vets

By Carman Peterson

cpeterson@barrowcountynews.com

UPDATED Feb. 7, 2010 9:45 a.m.

Jamie Keyes was an Army mom.

Her son Nathan was in the military for eight years, serving two tours of duty in Iraq. He followed in the footsteps of his grandfather and uncle, both of whom served in the military.

But when Nathan returned home with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, Keyes said she didn’t know what to do for him.

"These boys don’t come home with an instruction booklet – how to deal with them, how to respond to them, and I knew almost nothing about Post Traumatic Stress Disorder," Keyes said. "I knew nobody that had a son or daughter in the military, let alone one who came home with a disorder."

Nathan’s PTSD came to a head in August 2008, when he experienced a violent flashback in Florida. He is now in St. Augustine, serving a three-year prison sentence -- drastically shorter than the 20-year minimum he faced before Keyes began a letter-writing campaign educating people involved with the case about PTSD.

"That kind of got me going on personal advocacy," Keyes said. "Rather than crying over it, I decided to get out and make a difference."

Keyes believes her son never received the help he needed to readjust to civilian life. Now, the Statham grandmother has devoted herself to state- and nation-wide efforts to provide that readjustment for other soldiers returning home.

"Obviously they need a lot more support than they’re getting," Keyes said. "A lot of them are released from the military and having problems and not going to the VA, and a lot of them end up committing suicide or incarcerated... [We need to] do what we can to help them get their lives back instead of incarcerating them."

Among the projects Keyes is involved in is a jail diversion program being piloted in DeKalb County, where she volunteers on the advisory board. Georgia is one of 12 states implementing the diversion program, which directs veterans diagnosed with PTSD and charged with non-violent crimes into treatment and case management rather than incarceration.

She has issued a call for lawyers willing to donate their services to veterans with PTSD.

"If it hadn’t been for an attorney who was a vet, who heard about my son and offered to work for him pro bono, I don’t know what would have happened to my son," she said.

As National Guard soldiers headquartered in Barrow County approach their March homecoming, Keyes also hopes to start a local support group for families of military personnel and veterans.

"Many of these families are under a large amount of stress and are bearing up under it on their own," Keyes said.

Keyes has more work ahead of her: she’s awaiting the broadcast of a PBS episode of the documentary "In Their Boots" featuring Nathan’s story and speaking at a national convention in Orlando this spring.

"We’re all working together to find solutions, and that’s going to affect every vet in this state," Keyes said.

While Keyes spends her time working for our country’s fighting forces, she hopes her fellow Barrow County residents will help local veterans and their families adjust.

"There are many ways that the community can reach out and help them," she said. "It could come in the form of giving them jobs, affordable housing, childcare, household expenses, pro bono legal help, free services such as home repairs or modifications for vets who are disabled, donating to many of the veterans charities or free counseling... Something as simple as being a friend to a military spouse and letting them know that you are there for them when their loved one is deployed or at home after a deployment can make a huge difference."

cpeterson@barrowcountynews.com

UPDATED Feb. 7, 2010 9:45 a.m.

Jamie Keyes was an Army mom.

Her son Nathan was in the military for eight years, serving two tours of duty in Iraq. He followed in the footsteps of his grandfather and uncle, both of whom served in the military.

But when Nathan returned home with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, Keyes said she didn’t know what to do for him.

"These boys don’t come home with an instruction booklet – how to deal with them, how to respond to them, and I knew almost nothing about Post Traumatic Stress Disorder," Keyes said. "I knew nobody that had a son or daughter in the military, let alone one who came home with a disorder."

Nathan’s PTSD came to a head in August 2008, when he experienced a violent flashback in Florida. He is now in St. Augustine, serving a three-year prison sentence -- drastically shorter than the 20-year minimum he faced before Keyes began a letter-writing campaign educating people involved with the case about PTSD.

"That kind of got me going on personal advocacy," Keyes said. "Rather than crying over it, I decided to get out and make a difference."

Keyes believes her son never received the help he needed to readjust to civilian life. Now, the Statham grandmother has devoted herself to state- and nation-wide efforts to provide that readjustment for other soldiers returning home.

"Obviously they need a lot more support than they’re getting," Keyes said. "A lot of them are released from the military and having problems and not going to the VA, and a lot of them end up committing suicide or incarcerated... [We need to] do what we can to help them get their lives back instead of incarcerating them."

Among the projects Keyes is involved in is a jail diversion program being piloted in DeKalb County, where she volunteers on the advisory board. Georgia is one of 12 states implementing the diversion program, which directs veterans diagnosed with PTSD and charged with non-violent crimes into treatment and case management rather than incarceration.

She has issued a call for lawyers willing to donate their services to veterans with PTSD.

"If it hadn’t been for an attorney who was a vet, who heard about my son and offered to work for him pro bono, I don’t know what would have happened to my son," she said.

As National Guard soldiers headquartered in Barrow County approach their March homecoming, Keyes also hopes to start a local support group for families of military personnel and veterans.

"Many of these families are under a large amount of stress and are bearing up under it on their own," Keyes said.

Keyes has more work ahead of her: she’s awaiting the broadcast of a PBS episode of the documentary "In Their Boots" featuring Nathan’s story and speaking at a national convention in Orlando this spring.

"We’re all working together to find solutions, and that’s going to affect every vet in this state," Keyes said.

While Keyes spends her time working for our country’s fighting forces, she hopes her fellow Barrow County residents will help local veterans and their families adjust.

"There are many ways that the community can reach out and help them," she said. "It could come in the form of giving them jobs, affordable housing, childcare, household expenses, pro bono legal help, free services such as home repairs or modifications for vets who are disabled, donating to many of the veterans charities or free counseling... Something as simple as being a friend to a military spouse and letting them know that you are there for them when their loved one is deployed or at home after a deployment can make a huge difference."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

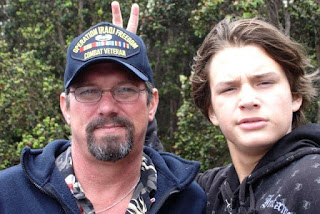

"Grandpa Pat & Kain"

"Kain-man" the jokester....

Pat Lamoureux - Iraq 2003

"Pat is an extraordinary, thoughtful, kind and generous man...not to mention a wonderful friend, in which one could always count upon to be there when in need." (words of a long time friend)

Pat's Family

Mica & Heather, grandson Kain