The Prozac, Paxil, Zoloft, Wellbutrin, Celexa, Effexor, Valium, Klonopin, Ativan, Restoril, Xanax, Adderall, Ritalin, Haldol, Risperdal, Seroquel, Ambien, Lunesta, Elavil, Trazodone War

As it approaches its tenth year, our nation’s longest war is showing signs of waning. Meanwhile, our soldiers are falling apart.

New York Magazaine

By Jennifer Senior Published Feb 6, 2011

The first time I meet David Booth, a 39-year-old former medic and surgeon’s assistant who retired this past spring after nineteen years in the active Army Reserve, I make the awkward mistake of proposing we go out to lunch. It seems a natural suggestion. The weather is still warm, and he has told me to meet him in the lobby of his office downtown, so I assume he wants to go out, not back to his desk, when I show up around noon. But it turns out that in the six months he has been at his job, Booth has never left his office in the middle of the day, except to run across the street, and he is simply too polite to say so. From the moment we step outside, it’s clear how unusual this excursion is for him. As we walk, he hews close to the buildings on his right (“If a building’s to my right, no one is going to walk by me on my right”), and when we arrive at the restaurant, he quietly takes a seat at the table closest to the door, his back against the wall. His large brown eyes immediately start darting around.

How’s your sleep?” I ask him.

“I don’t,” he answers.

Depending on the war, post-traumatic stress can have many expressions, but this war, because of its omnipresent suicide bombers and roadside explosives, seems to have disproportionately rendered its soldiers afraid of two things: driving and crowds. Movie theaters, subway cars, densely packed spaces—all can pose problems for soldiers, because marketplaces are frequent targets for explosions; so can any vehicle, because IEDs are this war’s lethal booby trap of choice. Booth manages his driving anxieties by leaving his Long Island home every morning at 4:30 a.m., when there’s no risk of traffic (especially under bridges, which militants in Iraq are always blowing up), and avoiding the right lane (in Afghanistan and Iraq, one generally drives in the middle of the road to avoid setting off IEDs). Once he gets to the city, Booth parks around the corner from his office and has managed to arrange his life so that he never encounters more than a handful of people. The only real logistical challenge is lunchtime, which he handles by ordering in, picking up from a grill across the street, or skipping entirely. I ask if he goes to restaurants in the off-hours. “Not very much,” he answers, pointing to two sets of scars, one near his jugular and the other stretching down his spinal column. “I reach for a glass, and I can’t feel pressure, so I’ll knock the glass over. It’s hard not to feel self-conscious.”

Click below for complete article

http://nymag.com/news/features/71277/

Sue Lamoureux's blog for her husband, J Patrick Lamoureux. Sue died on 24 August 2015.

PAT LAMOUREUX

PAT LAMOUREUX - One episode in a person's life, does not define the person.

Tuesday, February 8, 2011

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

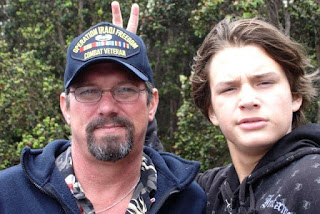

"Grandpa Pat & Kain"

"Kain-man" the jokester....

Pat Lamoureux - Iraq 2003

"Pat is an extraordinary, thoughtful, kind and generous man...not to mention a wonderful friend, in which one could always count upon to be there when in need." (words of a long time friend)

Pat's Family

Mica & Heather, grandson Kain