Battling the Inner Demons of War

03/25/2010

By Cordula Meyer

A photograph of PFC Joseph Dwyer in Iraq made him an American hero, but five years after returning home, mental combat wounds drove him to his death. He is not alone. In 2009, more than twice as many soldiers died by their own hands than were killed by the enemy in Iraq. But new types of therapy are giving others the chance for the peace he never had.

"In 2009, more than twice as many US servicemen and women committed suicide than were killed in combat in Iraq (334 and 149, respectively)."

On an afternoon in June 2008, police in Pinehurst, North Carolina, were dispatched to a white farmhouse. The town is set in an idyllic location, complete with woods, plantation houses and eight golf courses. Many of its inhabitants are retirees, so law enforcement officers generally don't have much to do. But, in the previous months, they had repeatedly been called to this particular address. Its owner, a 31-year-old man named Joe Dwyer, had been barricading himself in his house, where he kept several pistols and a semiautomatic rifle.

This time, the officers broke down the door. Once inside, they found Dwyer lying on the ground, covered in feces and urine, gasping for air. "Help me!" the young man begged the officers. "I can't breathe." Surrounding him were dozens of empty cans of Dust-Off, an aerosol spray meant to clean electronic equipment. But it can also be inhaled as a kind of sedative, which can cause heart and lung damage if repeated.

A taxi driver had alerted the police. She told them that, for months, she had been driving him to local shops every day to buy his cans of Dust-Off because he had wrecked his own car veering to avoid a roadside object he thought was an Iraqi bomb.

Joseph Dwyer was a giant of a man with reddish-brown hair. He died that same day while being rushed to the hospital. He was buried a few days later with military honors. While handing Dwyer's widow, Matina, the folded flag that had been draped over her husband's coffin as a mark of respect from the US Army, an officer fell to his knees in front of her.

Joe Dwyer, who had died so lonely and miserably, was an American hero. In March 2003, the front pages of newspapers across America featured a photo of Dwyer carrying a small Iraqi boy to safety shortly after a firefight. "It was the image of war that everyone wanted to see," says Warren Zinn, the photographer who took the picture. It was also the image that America wanted the rest of the world to see: a brave, compassionate US soldier doing something helpful and acting with the best of intentions in the Middle East. It just might be, however, that Joe Dwyer didn't outlive the war in Iraq precisely because he actually was the way America wanted to be seen.

The Soldiers' Epidemic

Matina Dwyer has short brown hair. A thin, silver cross hangs around her neck. "Joseph did not commit suicide," she says. "He died because of the combat wounds he sustained in his mind." Sitting in a restaurant in Pinehurst, Matina picks at her Caesar salad. It takes her a long time to finish each sentence. "I have peace knowing that he does not have to fight his horrible memories anymore, that he finally does not have to suffer so much," she says. "I can only bear that he is dead because this maybe was his way to help people."

Indeed, after meeting Joe Dwyer, a US Army psychiatrist began developing new methods for treating combat veterans who have been emotionally damaged by their combat experiences.

Joe Dwyer suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). More and more servicemen and women returning home to America -- but also to England and Germany -- are being diagnosed as suffering from PTSD. About one in every five US soldiers who returns home after a tour of duty in Iraq or Afghanistan later finds him- or herself battling traumatic neuroses. An estimated 300,000 US war veterans suffer from PTSD, though many don't seek medical help for fear that they will be classified as being mentally ill. According to the findings of a survey commissioned by the Rand Corporation, an American think tank, only half of those who can eventually overcome their reticence and seek medical help receive even the "barely adequate" treatment they require.

In 2009, more than twice as many US servicemen and women committed suicide than were killed in combat in Iraq (334 and 149, respectively). A year earlier, military doctors found that, each month, roughly 1,000 veterans were trying to take their own life. More than 100 veterans of the fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan have completely snapped after returning home and ended up killing others. A third of their victims were girlfriends, wives or other family members.

John Fortunato began seeing the first signs of this epidemic five years ago while working as a US Army psychiatrist at Fort Bliss, near El Paso, Texas. The young veterans returning from Iraq who came to see him spoke of being plagued day and night by feelings of guilt, panic and rage as well as dark thoughts.

Like any other Army psychiatrist, Fortunato prescribed medication to soldiers. If he had time, he would also speak with them. In most cases, though, Fortunato merely issued medical certificates that got his battle-scarred patients discharged from the army on the grounds that they had been deemed unfit for combat duty. In reality, though, by then, they were also unfit for life.

In 2006, when Fortunato found himself writing a certificate for a patient named Joe Dwyer, he starting wondering whether he was doing the right thing. "Dwyer was a great guy with a good sense of humor," Fortunato recalls. Dwyer's slow downward spiral prompted the psychiatrist to set up a center that aimed to turn emotionally wrecked combat veterans back into relatively normal human beings. The center's opening ceremony was held in 2007. Officers gave speeches, and a general cut the ceremonial ribbon.

(click here for complete article: http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/0,1518,685442,00.html )

Sue Lamoureux's blog for her husband, J Patrick Lamoureux. Sue died on 24 August 2015.

PAT LAMOUREUX

PAT LAMOUREUX - One episode in a person's life, does not define the person.

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

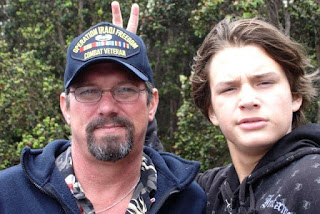

"Grandpa Pat & Kain"

"Kain-man" the jokester....

Pat Lamoureux - Iraq 2003

"Pat is an extraordinary, thoughtful, kind and generous man...not to mention a wonderful friend, in which one could always count upon to be there when in need." (words of a long time friend)

Pat's Family

Mica & Heather, grandson Kain