By Dahlia Lithwick

NEWSWEEK

Published Feb 11, 2010

From the magazine issue dated Feb 22, 2010

"Perhaps the inevitable conclusion here is the one nobody wants to say out loud: we have known for years that treatment works better than incarceration when it comes to criminal defendants with drug and mental-health problems."

The problem is hardly a new one, but we need only watch The Hurt Locker to refresh our collective memory: veterans return from war, having seen and survived unspeakable things, then try to adjust to civilian life with inadequate resources and support. Depending on the study you read, between 20 and 50 percent of veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars suffer from posttraumatic stress and other mental disorders—and half don't seek mental-health care. Those who do don't always receive the kind of care they need. The results of these systemic failures are increased instances of rape, assault, addiction, and other criminal acts that tangle up veterans in the criminal courts. The Department of Veterans Affairs estimates that veterans account for 10 percent of the people with criminal records.

The first "veterans' court" was launched in Buffalo, N.Y., in January 2008 by Judge Robert Russell. His program was based on the various "problem solving" tribunals around the country, ranging from specialized drug courts to mental-health and domestic-violence courts. Drug courts, for instance, integrate treatment with justice-system case management, and closely supervise and monitor participants. Studies show they have decreased recidivism rates as well as the cost of incarceration. In recent testimony before the House Veterans' Affairs Committee, Russell said his program teams veterans guilty of nonviolent felony or misdemeanor offenses with volunteer veteran mentors, requiring them to adhere to a strict schedule of rehabilitation programs and court appearances. One hundred and twenty veterans are enrolled in the Buffalo program; 90 percent of participants have successfully completed the program, and the recidivism rate is zero.

Since the Buffalo experiment was launched, 22 other cities and counties have created their own veterans' courts. The Senate is looking at legislation introduced by John Kerry and Lisa Murkowski to fund more veterans' courts for nonviolent offenders. Whether these will serve violent offenders as well is already a difficult issue for legislators and judges. The Buffalo court handles chiefly nonviolent offenses. But that may not solve the problems in Colorado Springs, Colo., where there have been 15 former GIs arrested in connection with a dozen murders over the past five years. These are guys who have never been involved in the criminal-justice system in their lives. They come home from war profoundly different men.

That's why Robert Alvarez, a psychotherapist with the Wounded Warrior program at Fort Carson, recently told a Denver newspaper that it's a mistake to carve the most violent offenders out of the proposed veterans' court in Colorado: "The violent offenders need help more than anybody … the very skills these people are taught to follow in combat are the skills that are a risk at home." If you are going to create special judicial programs to help veterans, does it make sense to give special services only to those who need help the least?

The bigger issue with the veterans' courts has been raised by the American Civil Liberties Union, which objects to the creation of a unique legal class of criminals based on their status as veterans. Thus, Lee Rowland of the ACLU of Nevada opposes the proposed state veterans'-court bill because it provides "an automatic free pass based on military status to certain criminal-defense rights that others don't have." Mark Silverstein, legal director of the Colorado ACLU, explains that the legal category of "veteran" is both too broad and too narrow, sweeping in both Vietnam and World War II veterans who have very different experiences, but excluding nonveterans who also suffer from PTSD and aren't eligible for any special courts.

Perhaps the inevitable conclusion here is the one nobody wants to say out loud: we have known for years that treatment works better than incarceration when it comes to criminal defendants with drug and mental-health problems. We also know that close supervision and monitoring work better than casting our most vulnerable citizens adrift. Veterans deserve special treatment for their service, and the fact that veterans' courts seem to work as well as they do suggests that politicians needn't justify their existence beyond that fact. But whether we really want to create first- and -second-class criminal-justice services, and whether we can truly draw any principled line between nonviolent veterans and violent ones in the judicial treatment they receive, are not easy political questions, but thorny legal ones.

(article from http://www.newsweek.com/id/233415.)

Sue Lamoureux's blog for her husband, J Patrick Lamoureux. Sue died on 24 August 2015.

PAT LAMOUREUX

PAT LAMOUREUX - One episode in a person's life, does not define the person.

Saturday, February 20, 2010

A Separate Peace - Why Veterans Deserve Special Courts

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

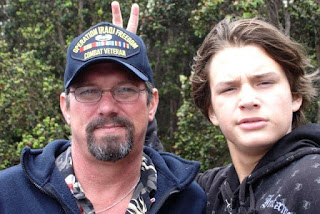

"Grandpa Pat & Kain"

"Kain-man" the jokester....

Pat Lamoureux - Iraq 2003

"Pat is an extraordinary, thoughtful, kind and generous man...not to mention a wonderful friend, in which one could always count upon to be there when in need." (words of a long time friend)

Pat's Family

Mica & Heather, grandson Kain

No comments:

Post a Comment